In my previous post, I referenced a White Paper (Duran, Plotkin, Potter, Rosen) published by the Justice Center that explores the intersection between reintegration and employment. With this post, I’d like to delve a bit deeper into their recommendations and the preliminary results from two test communities.

In my previous post, I referenced a White Paper (Duran, Plotkin, Potter, Rosen) published by the Justice Center that explores the intersection between reintegration and employment. With this post, I’d like to delve a bit deeper into their recommendations and the preliminary results from two test communities.

The paper’s core thesis can be boiled down to one overarching recommendation:

“There is no clearer message in this white paper than the need for validated assessments to inform decision making for behind-the-bars programming, community supervision, and reentry planning—including employment services.”

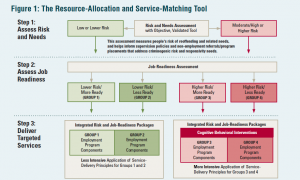

The authors then propose a sequential assessment tool that begins with a validated Risk, Need, Responsivity Assessment and then follows with Job-Readiness Assessments. The overarching goal with this process is to:

- Triage and direct scarce employment services to clients who pose the greatest risk;

- Minimize ‘over-treatment’ of offenders who present little risk.

From this sequential assessment process, the authors then recommend that employment services be divided into four broad categories of clients:

- Moderate to High Risk, Low Job Readiness: This population of clients present both the greatest risk to re-offend and have the most significant barriers to employment, often for the same reasons, including: substance abuse, mental illness, negative associates, and ‘criminal thinking’. Employment and supervision services for this group would be both intensive and phased. Working together, the Probation Officer and Employment Specialist may decide that immediate needs, such as substance abuse treatment, must be first addressed before engaging employment services. Clients within this category of services also typically need a higher degree of supervision and service engagement, with frequent interactions that model pro-social behaviors and positive reinforcement. Initially, these clients’ employment services would likely focus on job-readiness services (soft-skill workshops, on-the-job training programs, work crews, etc.) rather than market-based job search, placement, and retention services.

- Moderate to High Risk, High Job Readiness: This population presents equally high-risk to re-offense as the first group but is more-ready to move into employment search and retention services. With this group, treatment services to address criminogenic needs would likely be integrated into employment services and schedules. These clients still would need intensive engagement, supervision, and pro-social activities, but would be transitioned into market-based employment more quickly than the first group.

- Low Risk, Low Job Readiness: This population presents low risk to reoffend but with significant employment barriers. The authors make clear that although this population may require more intensive support and services to secure employment, they should not be grouped with the higher risk individuals. (There is growing evidence that mixing risk populations can actually increase this group’s risk of offense). Supervision of these individuals also should not interfere with the individuals’ capacity to access their positive peer networks and families.

- Low Risk, High Job Readiness: This population may need only modest support to secure and retain employment. This might include job-matching services, resume preparation, or interview practice, but the intensity/frequency should be low. Individuals in this category should also receive minimal supervision. Overarching conclusion with this group: allow them space, they should do just fine.

The White Paper is clear that these four groupings should not replace the individuation of services. Within the broader framework of intensity, timing, and incentives, services should still be targeted and strategically phased to meet the needs of the individual client.

The White Paper is clear that these four groupings should not replace the individuation of services. Within the broader framework of intensity, timing, and incentives, services should still be targeted and strategically phased to meet the needs of the individual client.

Finally, the White Paper makes a compelling case that treatment that targets the criminogenic needs of high-risk individuals, such as Cognitive Based Therapy, should be integrated into the employment program services. This may seem like a stretch, given the different mandates of organizations that provide treatment versus employment readiness programs. The authors, however, suggest that employment programs, with funding and support, are well-suited to integrate CBT into their program structures.

The White Paper was published in 2013 with the promise of testing these recommendations in two pilot communities.

In April of this past year, the National Reentry Resource Center published a preliminary report from the two test sites. The preliminary report did not provide outcome data; it’s still too early to generate meaningful results. Rather, the Report focused on four questions that have emerged from the early implementation of the recommendations. Not surprisingly, these questions are more about process than actual services:

- Is our leadership committed to a collaborative approach?

- Do we conduct timely risk and needs assessments and job-readiness screenings?

- Have we conducted a comprehensive process analysis and inventory of employment services that are provided pre- and post-release?

- Do we have a coordinated process for making service referrals and tracking data?

Let’s take unpack each of these questions.

- Collaboration: The preliminary report highlights the importance of leadership in building collaborative initiatives. Reintegration services cross multiple governmental and non-governmental agencies and programs. For these services to be integrated, state and local leaders need to commit to the work of collaboration with their time, funding, and mutual accountability.

- Timely Assessments: As is mentioned above, the White Paper starts with a core recommendation: use assessments to determine services. Collaborating agencies must be able to share–and understand–the assessments’ information, which may require cross-trainings. Finally, agencies should have equal access to good data about the number (and geographic distribution) or reintegrating individuals. This will allow for better allocation of resources to meet existing needs.

- Employment Services and Process Inventory: For services to be timely (as early as possible upon release for high-risk individuals), system stakeholders need to have an understanding of how offenders ‘move through’ the system and what resources and programming are available at each step right through to release. Agencies should also be evaluating whether resources are allocated efficiently to meet the needs, particularly of the high-risk population.

- Effective Referral Processes: The preliminary report highlights the need for an agency or program to take the lead on coordinating and tracking referrals. This agency may vary from community to community but the overarching goal is to ensure that referrals are matched to the needs and risks of the individual; referrals are tracked for compliance; and information is shared across collaborating agencies. The lead agency will also be best suited to identify gaps in services that can be targeted for grants and funding.

This National Reentry Resource Center’s preliminary report covers the lessons learned during the first year of implementation. The pilot projects will continue to test the White Paper’s recommendations for two more years.

In the next post, I will look at how prisons can support employment readiness.